Amazake made from rice malt is like a drinkable beauty serum

What comes to mind when you think of amazake?

Do you think of sweetness? Celebratory shrine functions? Perhaps the Japanese new year?

The amazake you are accustomed to may have been made from sake lees.However, Tokyo Port Brewery’s “Tokyo Amazake†is made

solely from rice and rice malt.This brew has a cleanly sweet taste that calls to mind notes of yogurt.Rich in Vitamin B, essential

amino acids, and glucose, amazake is often referred to as a “drinkable beauty serum.â€

Located just 10 minutes walk from Tamachi Station is a small brewery that lies tucked away behind the concrete jungle

Pass by the array of skyscrapers in Minato-ku and enter a sidestreet to escape the hustle and bustle and find a calm, quiet thoroughfare. There you will soon spot a building with a hanging ball of spruce sprigs. This is your landmark for Tokyo Port Brewery. The dainty, well-appointed shop is stylish, suggesting a blend of tradition and modernity. The brewery itself is opposite, facing the road. This four-story building is so compact that you really question how they could pack a brewery in there. Yet this commitment to small scale is what Tokyo Port Brewery is all about.

Though founded in the Edo period, the company was shuttered for many years. Now its signature brews are lining store shelves after 100 years

Though appearing as a simple and modern shop, Tokyo Port Brewery is in fact a historic producer dating quite a way back. It was founded in 1812, during the Edo period, under the name Wakamatsuya. The shop was frequented by historic greats like Saigo Takamori and Katsu Kaishu. As the times changed and liquor taxes and other measures were imposed, the company shuttered in 1911, just on the verge of its 100th anniversary. 100 years later, in 2011, the 7th generation descendant of that brewery, Shun’ichi Saito, decided to breathe new life into Tokyo Port Brewery.

Alongside company president Shun’ichi Saito, who brought the brewery back to life after 100 years’ time, is one man who has handled the technical reins of the enterprise. Introducing Yoshimi Terasawa, the chief brewer of the firm.

We sat down with him to learn about the backstory to the reboot of the company and what his approach to brewing is.

Restarting a brewery as a way to revitalize a faded shopping district

Terasawa told me that Saito was an officer of the organization running the shopping district, and wanted to get the local economy going. Terasawa explained the genesis of the brewery as follows: As more and more traditional shopping streets around Japan fall on hard times, the ones that stood out for drawing a steady clientele were souvenir shops and breweries. Saito recalled that one of his ancestors had been in the brewing business, so he thought it would be quite novel and unique to set up a brewery in the middle of Tokyo, and it might revitalize the shopping district.

The space was just 73 square meters in size, and going back to brewing brought many unknowns.

A problem suddenly presented itself: the lack of space to allocate to the new venture. They had just 73 square meters to work with. Saito searched for an effective means of making the best use of this space, and he selected Terasawa as the man to make this dream a reality. Terasawa had considerable experience at a major brewery and had then gone on to develop Japanese sake at a microbrewery. He says that he knew exactly what to do as soon as he set eyes on the space.

Building up a microbrewery like this might be a testament to my life’s work, I thought.

Terasawa laughs, saying he originally rejected the offer. Apparently, small-scale microbreweries can really struggle to make ends meet, since they produce minimal quantities. Yet Saito continued paying visits to Terasawa in the hopes of persuading him. It was at this time that the latter had taken the gold medal at the New Sake Appraisal competition for a microbrewed sake. “After winning the award, I decided to make it my mission to demonstrate that small-scale breweries can make excellent sake. With microbreweries, you cut out the red tape and can get the product directly into the hands of the consumer.†With that, their tandem project for locally-brewed Tokyo sake began.

This amazake made entirely in Tokyo is also Japan’s priciest!

Saito and Terasawa emphasized one key point in producing this brew: that it be made entirely in Tokyo. The rice, malt, and water are all sourced locally. Local Tokyo tap water is used because its content is perfect for sake brewing, they say. Terasawa brought expertise not only in Japanese sake, but in the amazake variety. Apparently, Tokyo Amazake is based on a recipe developed by Terasawa’s own mother for the drinks they brewed at home. Terasawa beams with pride when he says, “It’s entirely handmade, so I would venture to guess that ours is the most expensive amazake in Japan.â€

Milling

Brown rice is polished of its hulls to produce fine white rice. The key here is storing the rice at a low temperature.

Mashing and fermentation

Twenty hours are devoted to stirring the steamed rice, rice malt, and water in a fermenting mash tank. The quantity of rice malt dictates the sweetness.

Filling the bottles

The product is submerged in water heated to 65℃ in order to sterilize it, then bottled and inspected.

Steaming

Washing the rice and rinsing it of water is done under a strictly time-controlled process. It is then moved to steaming baskets.

Tweaking the flavor

After fermentation, the Brix levels and sweetness are measured in specialized machinery and the flavor is adjusted.

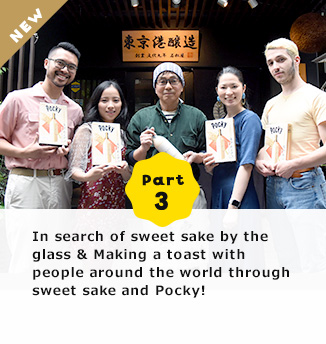

Each bottle of this amazake brew is produced with care by hand. Only 70 bottles are made over the span of two weeks. The two men behind Tokyo Port Brewery insisted that they refuse to mass produce, no matter how popular it may become. They told me it’s not about pure profit, but about creating an intangible asset in the form of local culture and history. It is that very commitment that imparts the amazake with such a unique and delicious flavor.

Can you believe there is an amazake brewed locally in Tokyo? I was moved by this duo’s commitment to the craft.

“It’s not about making money. We want to contribute to the culture.â€

I was so impressed by their enthusiasm that I have been telling all my friends about this new brewery.